Close

By Giannis Fyrogenis, Project Manager at reframe.food

Every morning, farmers across Europe wake up knowing they face a choice that shouldn’t exist: feed the world or protect their own health. The statistics tell a story that agricultural communities have lived with for decades, written in chronic illness records and health surveys that reveal an occupational crisis hiding in plain sight.

The health data paints a grim picture. Over 60% of agricultural workers report having chronic diseases that limit their work. Cardiovascular disease shows up again and again. When the EU surveyed workers back in 2012, agriculture topped the list of sectors where workers said their job was damaging their health, by a significant margin.

The reason isn’t hard to find. These workers handle pesticides designed to eliminate pests and weeds on a daily basis. The human body inevitably suffers from this constant exposure.

The acute poisoning rates are staggering. Agricultural workers experience pesticide poisoning 37 times more often than workers in other industries. That number bears repeating. 37 times. These poisonings aren’t minor incidents. They mean rushed trips to the hospital, days or weeks unable to work, and in the worst cases, death. The symptoms come on fast and hard: blinding headaches, vomiting, skin that feels like it’s on fire, lungs that won’t fill properly. According to a 2022 study, pesticides kill around 220,000 people globally each year. The majority? Farm workers.

But it’s the slow poisoning that’s perhaps even more insidious. Years of low-level exposure that disrupts hormones, triggers asthma, and damages kidneys and livers. The kind of damage that builds up so gradually you don’t notice until it’s too late. This is what farmers endure to keep food systems running and shelves stocked.

Here’s what makes it worse: research shows that 57% of farmers admit they cut corners on safety when they’re exhausted. Which is basically always, because farming is exhausting work. The average age of European farmers? 58.1 years. So there’s an aging workforce, with slowing reflexes, handling chemicals that require absolute precision. It’s a disaster that’s happening every single day.

Farmer treating apple trees with pesticides in orchard.

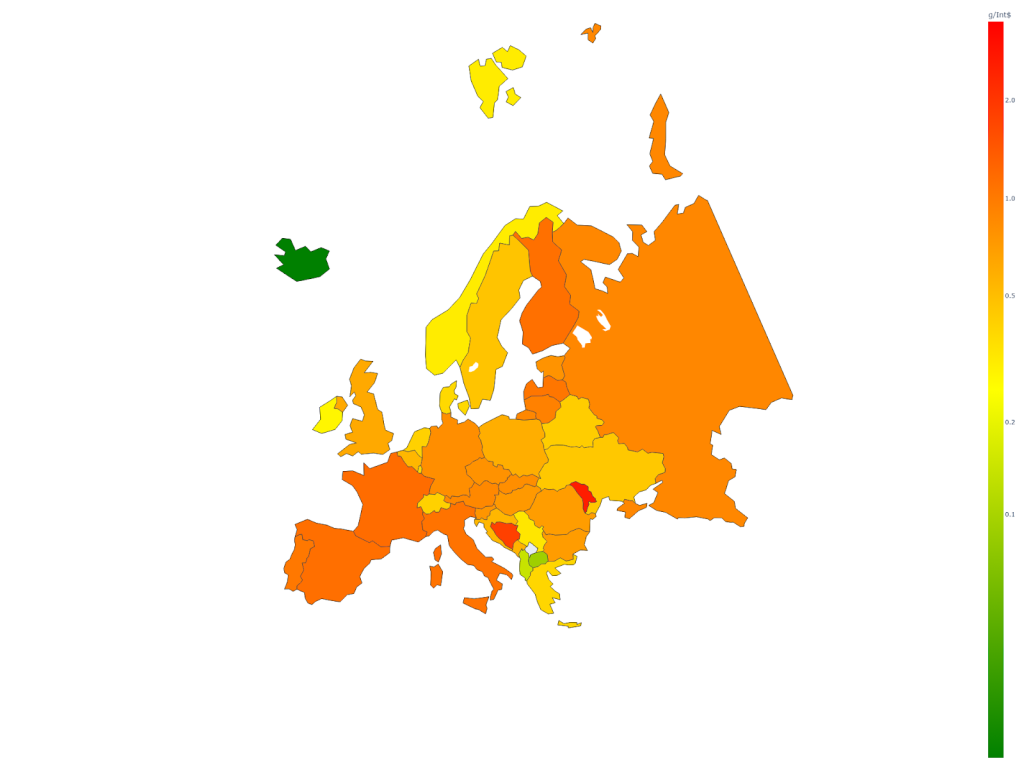

Recent FAO data reveals something remarkable. The variation in pesticide use across Europe defies expectations. Measured per dollar of agricultural production, the disparities are enormous. Iceland uses 0.01 grams per international dollar. The Faroe Islands use 3.48 grams, a 348-fold difference for what is fundamentally the same profession.

Look at where the big producers fall: France uses 1.16 g/Int$, Spain 1.12, Italy 1.08. These farmers face significantly higher chemical exposure than their counterparts elsewhere. Then there’s Denmark at 0.38, Ireland at 0.28, and the Netherlands at 0.41. They’re producing massive amounts of food with a fraction of the chemical load.

What does this tell us? That productive agriculture clearly doesn’t require excessive pesticide use. Some countries are already proving it.

Pesticide Use per Unit of Agricultural Production Value in Europe (2023)

This is where projects like Smart Droplets become genuinely exciting. They’re not just trying to revolutionize farming. They’re also trying to save farmers’ lives.

The concept is simple. Take existing tractors, retrofit them with autonomous systems. Let farmers run them remotely instead of sitting in a chemical fog. Use AI to spray only where it’s needed instead of blanket-bombing entire fields. Add direct injection systems so nobody has to hand-mix concentrated pesticides anymore (which, by the way, is when most acute poisonings happen).

The numbers are promising; up to 30% reduction in pesticide use overall. But even lesser savings would be worth it if it meant farmers could do their job without poisoning themselves.

What really matters is that this technology could bring Spanish and Italian farmers the same low-exposure conditions that Danish farmers already enjoy. This isn’t theoretical; the system has been successfully tested in Catalonia and Lithuania.

The technology is close to ready for deployment. The only question is how fast it can reach the fields where farmers are still making that impossible choice between their livelihood and their life. Every day of delay is another day of unnecessary exposure, another contribution to those 220,000 annual deaths.

Farmers feed us. The least we can do is make sure that feeding us doesn’t kill them.

References