Close

By Giannis Fyrogenis, Project Manager at reframe.food

Recent years have seen a reckoning with the chemical intensity of modern agriculture. Excessive pesticide and fertiliser use has become the de facto industry standard, but it comes at a heavy cost: polluting soil, water, and air and harming ecosystems and human health. Europe’s Green Deal and Farm‑to‑Fork strategy put numbers on the ambition, cut the use and risk of chemical pesticides by 50 % and reduce fertiliser use by 20 % by 2030. Delivering on those ambitions requires more than good intentions; it demands new technologies, smarter policies, and a willingness to work with nature rather than against it.

Chemical pesticides make farming easier in the short term, but their long‑term externalities are profound. The EU’s progress report on pesticide reduction shows that from 2018–2023, the use and risk of chemical pesticides fell by 58 % relative to the 2015–2017 baseline. The use of more hazardous pesticides declined by 27 % over the same period. These reductions suggest that Europe is on track to meet its 2030 targets, yet the gains hide uneven adoption across member states and resistance from farm lobbies. A proposal for a Sustainable Use Regulation (SUR), which would have made the 50 % target legally binding, faced fierce lobbying and was withdrawn in February 2024.

Civil‑society groups argued that postponing binding rules simply delays the inevitable. PAN Europe notes that the SUR was essentially a more enforceable version of the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Directive (SUD), in place since 2009, and that further delays will only worsen the environmental and health burden. The abandoned regulation would have complemented existing measures under the SUD, such as the requirement that all professional farmers implement integrated pest management (IPM) and prioritise non‑chemical methods. Without a strong regulatory stick, progress depends on market incentives, consumer pressure, and technological innovation.

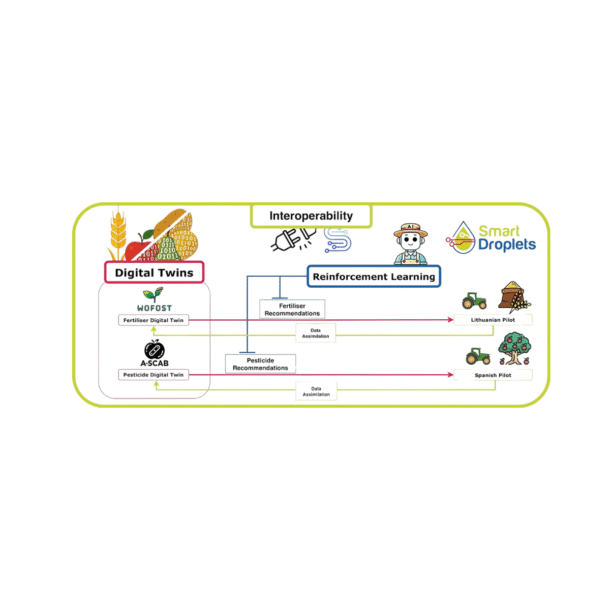

The Smart Droplets project, a Horizon Europe initiative, illustrates how cutting‑edge technology can align agricultural productivity with sustainability. The project’s description notes that current spraying practices are resource‑intensive and that excessive pesticide use causes severe environmental impact. Smart Droplets aims to reduce chemical waste by combining data infrastructures, artificial intelligence (AI) models, digital twins, and robotics. Its digital platform will integrate diverse data streams and use crop‑growth and disease models to recommend optimal spraying strategies, including variable-rate application and anomaly detection. Direct‑injection spraying technology allows the separate application of different chemicals, dramatically reducing off‑target spraying. By retrofitting autonomous tractors with sensors and linking them to AI‑driven digital twins, the project hopes to achieve a 20 % reduction in chemical use and make precision spraying commercially viable.

These innovations matter because they match high‑resolution data with the EU’s ambition to halve pesticide use. They also align with FORTUNA, a three‑year project launched in January 2024 to identify research gaps for pesticide‑use reduction. FORTUNA’s brief emphasises that the Farm‑to‑Fork strategy aims to decrease the overall use and risk of chemical pesticides by 50 % and reduce more hazardous pesticides by 50 %. The consortium aims to push beyond those targets by promoting integrated pest management and exploring socio‑economic and biological alternatives.

Not every solution is high‑tech. Farmers participating in the EU‑funded IPMWORKS project demonstrate that integrated pest management can dramatically reduce chemical use without sacrificing yields. In the Portuguese town of Tourinha, farmer Bruno Neves encourages populations of ladybirds and hoverflies to thrive. IPM combines crop rotation, pest‑resistant varieties, and biological controls so that pesticides are used sparingly and in ways that minimise risks to humans and beneficial organisms. Neves reports that by adopting IPM, he sprays only three or four times a year, whereas neighbouring farms spray twice a week. 0Coordinators of IPMWORKS note that holistic IPM is cost‑effective and often increases profitability, and scaling it up could realistically cut pesticide use by 50 % without decreasing food security.

The European Commission emphasises that IPM is a cornerstone of the SUD. IPM involves an integrated approach that uses all available information, tools, and methods. Pesticides should be applied only when economically and ecologically justified, with preference given to biological, physical, and other non‑chemical methods. The principles include crop rotation, balanced fertilisation, hygiene measures, monitoring, and threshold‑based interventions. These guidelines show that sustainable agriculture is as much about management practices as it is about cutting‑edge tools.

While producers innovate, consumers also influence the pesticide landscape. The Environmental Working Group (EWG) publishes an annual Shopper’s Guide to Pesticides in Produce. In the 2025 edition, EWG found that over 75 % of non‑organic fruits and vegetables contain pesticide residues. However, almost 60 % of samples in the “Clean Fifteen” list had no detectable pesticide residues, and the organisation now weighs the toxicity of detected pesticides when ranking produce. Potatoes and blackberries entered the “Dirty Dozen” because nearly 90 % of potatoes contain chlorpropham, a chemical banned in the EU. EWG advises that buying organic versions of high‑residue produce or washing produce thoroughly can reduce exposure.

This consumer‑facing information dovetails with EU objectives. By creating market demand for lower‑residue produce, shoppers can encourage farmers and retailers to shift toward sustainable practices. Improved labelling and traceability would further empower consumers to make informed choices.

Europe’s pesticide challenge will not be solved by a single innovation or policy. Regulatory frameworks, such as the SUD and the (now‑withdrawn) SUR, set targets and promote IPM but need stronger enforcement and integration with the Common Agricultural Policy. Technological projects like Smart Droplets show that AI, digital twins and robotics can translate data into precise, efficient spraying strategies. Grass‑roots initiatives such as IPMWORKS demonstrate that farmers can cut chemicals by working with nature, and they highlight the importance of peer networks and training. Finally, consumer awareness through guides like the EWG’s encourages demand for pesticide‑safe food and signals to producers that sustainability matters.

Reducing pesticides is not just an environmental imperative; it is a health, economic, and social necessity. Meeting the Green Deal’s 2030 targets will require coordinated action from policymakers, researchers, farmers, and consumers. By aligning smart technology with natural processes and informed consumption, agriculture can become both productive and ecologically sound. The next decade offers a pivotal opportunity to move from aspirations to action, turning Europe’s green ambitions into reality.